The trade war, pandemic and war in Ukraine have triggered a paradigm shift in how supply chains are managed, with some manufacturing production capacity being reshored and more being relocated to geopolitical allies through nearshoring and friendshoring. Just-in-time supply chain management is being replaced by just-in-case, with supply chain resilience becoming a top priority for companies. We take a look at the unique opportunity that nearshoring presents for the Mexican economy as a broad range of sectors and companies stand to benefit from supply chain reorganisation.

Recent changes in supply chain management reflect a reversal of the globalisation and offshoring trend that kicked off in earnest with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 and accelerated with China's accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. NAFTA made it much easier for manufacturers to shift production facilities from the US to Mexico where they could take advantage of lower costs while retaining close proximity to the end customer. Trade between the two countries trebled between 1994 and 2001. While Mexico's trade with the US continued to grow, it slowed meaningfully as China took over as the dominant destination for offshoring and quickly became America's largest trading partner.

Various US administrations have tried to address the US trade deficit with China and what they saw as unfair trade practices impacting domestic manufacturing employment. However, it was when Donald Trump was elected in 2016 that the trade war really escalated, with tariffs applied to a wide range of goods imported from China. The fragility of long and complex supply chains was exposed during the pandemic, and Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine showed the enormous risks and vulnerabilities of being overly reliant on geopolitical adversaries for the supply of strategic goods. The trade war, pandemic and war in Ukraine have triggered a paradigm shift in how supply chains are managed with some manufacturing production capacity being reshored and more being relocated to geopolitical allies through nearshoring and friendshoring.

Reshoring would be the preferred outcome for the US government, as it boosts the economy and creates jobs. However, the primary rationale for offshoring in the first place was the significant cost advantages of producing abroad, and US manufacturing wages remain considerably higher than in alternative countries across emerging markets. A tight labour market further complicates the large-scale relocation of manufacturing capacity back to the US, and the prevailing anti-immigration sentiment is unlikely to provide any relief in the near future. Therefore, the majority of investment is likely to go into nearshoring in Mexico as well as expansions in other Asian markets such as Vietnam and India.

A nearshoring case study − Mexico

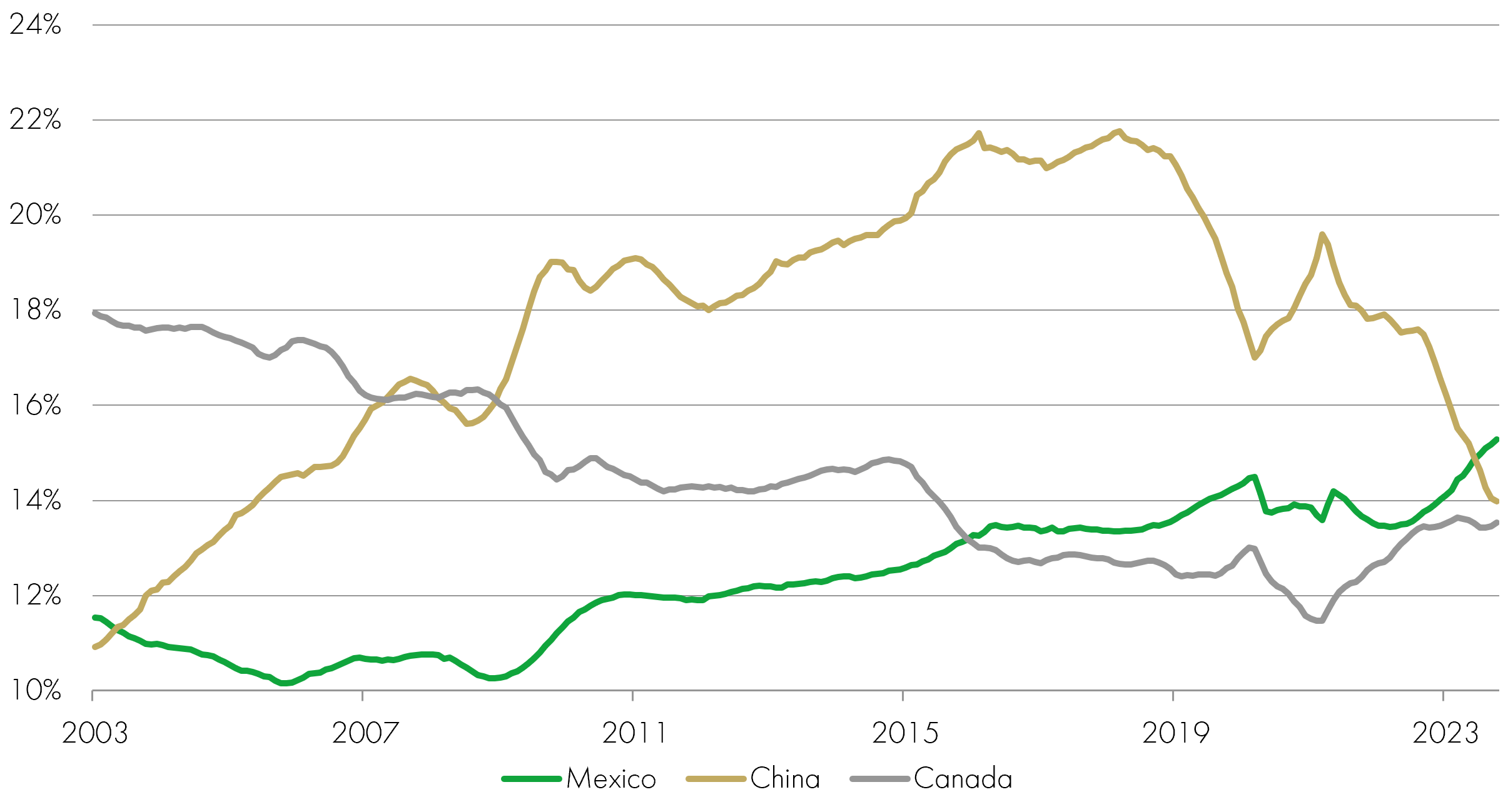

Mexico is clearly in a very strong position to receive additional investment as US-China decoupling continues and global companies reorientate supply chains. Mexico's competitive advantages as a manufacturing hub are well established and it has been gaining share of US imports for more than a decade − China's manufacturing wages exceeded those in Mexico back in 2013, and by 2040 China's working age population is expected to shrink by 12% while Mexico's will be 12% larger. The wage differential is likely to remain firmly in Mexico's favour. Mexico also has free-trade agreements with 50 countries, making it an ideal place from which to export not only to the US but much of the rest of the world.

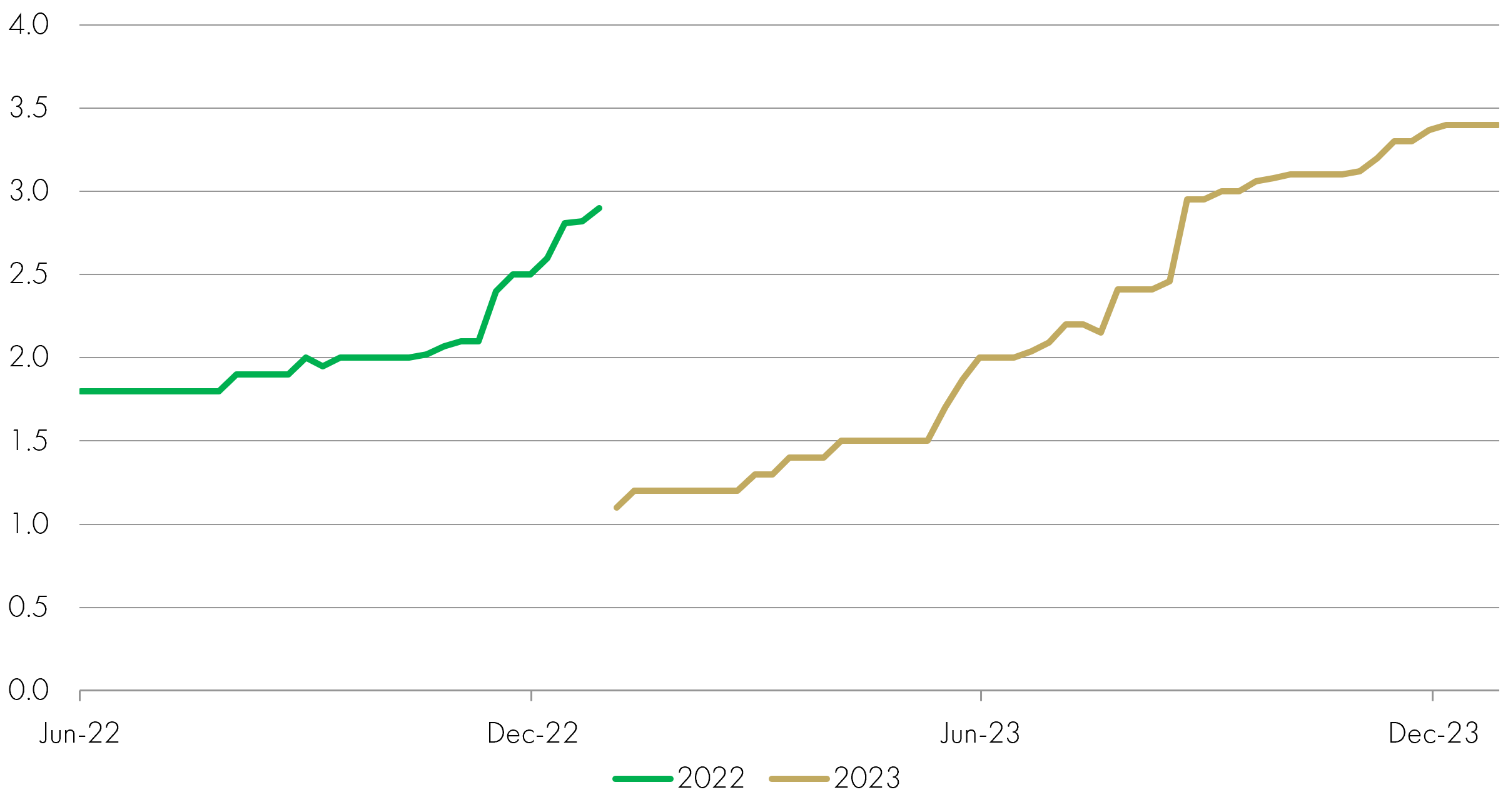

The impacts of nearshoring will be felt broadly across the economy; in the first instance this shows up in higher exports − this is already clear in the data, and we expect Mexico to continue to gain share of US imports in the years ahead. In 2023, Mexico once again became America's number-one trading partner, nearly two decades after it was overtaken by China. Every 1% share that Mexico gains in US imports provides a boost of over 1% to Mexico's economy and that has been a key driver behind the growth upgrades we have seen in recent years. Donald Trump has recently talked about hiking tariffs on all Chinese imports to 60% − while China's share of US imports has already fallen from a peak of 22% in 2017 to below 15%, under the current tariff regime their share of imports is expected to fall to just 10% by 2030. If tariffs were increased to 60%, this could fall very close to zero by the end of the decade.

Market share of US imports (12-month average)

Source: US Census Bureau, February 2024.

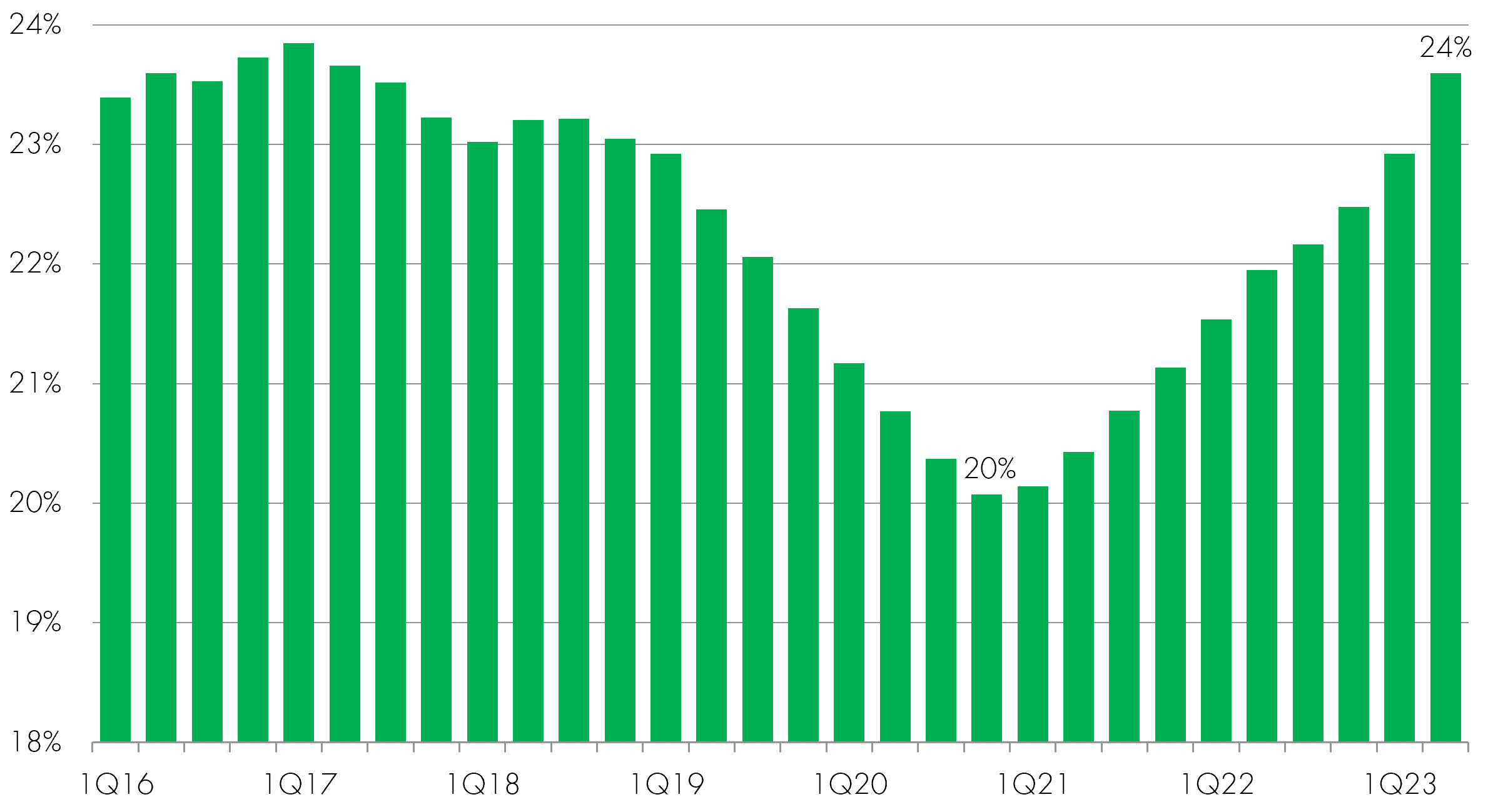

As capacity utilisation rises, investment in additional supply will be required. Through the first half of president Andrés Manuel López Obrador's (AMLO) six-year term, investment as a proportion of GDP edged lower as the private sector held back investment. However, over the last three years this has recovered sharply and with new projects being announced regularly it should continue to move higher. Moreover, under a new president later this year we would expect a more constructive relationship with the business community and a subsequent acceleration in capex. New projects worth $70 billion were announced last year − the one capturing the headlines was Tesla’s $5 billion gigafactory, although this was matched by a Chinese company's plan to invest $5 billion in industrial real estate and surpassed by a Texan energy company's $14 billion liquified natural gas plant. New announcements have continued this year, with Volkswagen committing a further $1 billion to expand its electric vehicle production. Industrial real estate companies operating in the north of the country are almost completely sold out and are bringing forward expansion plans in order to meet surging demand.

Mexico: investment as % of GDP

Source: INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography), February 2024

Finally, as new projects break ground, we would expect to see a boost to consumption as new jobs are created and more workers migrate into formal employment – informal workers outnumber formal workers by nearly two to one. Formalisation of the workforce will have wide ranging benefits, from increasing social security coverage to higher government revenues through greater tax collection. More important, however, will be rising levels of bancarisation – the percentage of the population holding a bank account. Nearly half of Mexican adults don’t have a bank account. Providing access to credit to an underleveraged population can help consumption become a key driver of growth, alongside activities more directly linked to nearshoring such as exports and investments.

There has been a surprising lack of government support to help companies take advantage of the nearshoring opportunity and much of the progress to date has happened despite the government rather than because of it. Again, we would expect this to improve under a new president. Frontrunner and former governor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum, is already engaging with companies to determine what policy support is required to maximise the opportunities that nearshoring presents.

The trend of nearshoring is firmly entrenched, presenting a unique opportunity for the Mexican economy and a broad range of sectors and companies to benefit from the vast potential of ongoing supply chain reorganisation.

GDP estimates, Mexico (% yoy)

Source: Bloomberg, as at February 2024.

KEY RISKS

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and the income generated from it can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. You may get back less than you originally invested.

The issue of units/shares in Liontrust Funds may be subject to an initial charge, which will have an impact on the realisable value of the investment, particularly in the short term. Investments should always be considered as long term.

The Funds managed by the Global Fundamental Team:

May hold overseas investments that may carry a higher currency risk. They are valued by reference to their local currency which may move up or down when compared to the currency of a Fund. May encounter liquidity constraints from time to time. The spread between the price you buy and sell shares will reflect the less liquid nature of the underlying holdings. May have a concentrated portfolio, i.e. hold a limited number of investments or have significant sector or factor exposures. If one of these investments or sectors / factors fall in value this can have a greater impact on the Fund's value than if it held a larger number of investments across a more diversified portfolio. May invest in smaller companies and may invest a small proportion (less than 10%) of the Fund in unlisted securities. There may be liquidity constraints in these securities from time to time, i.e. in certain circumstances, the fund may not be able to sell a position for full value or at all in the short term. This may affect performance and could cause the fund to defer or suspend redemptions of its shares. May invest in emerging markets which carries a higher risk than investment in more developed countries. This may result in higher volatility and larger drops in the value of a fund over the short term. Certain countries have a higher risk of the imposition of financial and economic sanctions on them which may have a significant economic impact on any company operating, or based, in these countries and their ability to trade as normal. Any such sanctions may cause the value of the investments in the fund to fall significantly and may result in liquidity issues which could prevent the fund from meeting redemptions. May hold Bonds. Bonds are affected by changes in interest rates and their value and the income they generate can rise or fall as a result; The creditworthiness of a bond issuer may also affect that bond's value. Bonds that produce a higher level of income usually also carry greater risk as such bond issuers may have difficulty in paying their debts. The value of a bond would be significantly affected if the issuer either refused to pay or was unable to pay. Outside of normal conditions, may hold higher levels of cash which may be deposited with several credit counterparties (e.g. international banks). A credit risk arises should one or more of these counterparties be unable to return the deposited cash. May be exposed to Counterparty Risk: any derivative contract, including FX hedging, may be at risk if the counterparty fails. Do not guarantee a level of income. The risks detailed above are reflective of the full range of Funds managed by the Global Fundamental Team and not all of the risks listed are applicable to each individual Fund. For the risks associated with an individual Fund, please refer to its Key Investor Information Document (KIID)/PRIIP KID.

DISCLAIMER

This is a marketing communication. Before making an investment, you should read the relevant Prospectus and the Key Investor Information Document (KIID), which provide full product details including investment charges and risks. These documents can be obtained, free of charge, from www.liontrust.co.uk or direct from Liontrust. Always research your own investments. If you are not a professional investor please consult a regulated financial adviser regarding the suitability of such an investment for you and your personal circumstances.

This should not be construed as advice for investment in any product or security mentioned, an offer to buy or sell units/shares of Funds mentioned, or a solicitation to purchase securities in any company or investment product. Examples of stocks are provided for general information only to demonstrate our investment philosophy. The investment being promoted is for units in a fund, not directly in the underlying assets. It contains information and analysis that is believed to be accurate at the time of publication, but is subject to change without notice.