Anyone who has suffered bemused looks when trying to pay with cash in a shop or pub will be aware how rapidly we are moving towards a cashless society. Increasing financial resilience remains a key theme across our Sustainable Future portfolios and as part of this, we believe the shift from cash to digital payments provides overall net benefits to society. With this in mind, we are looking to invest in profitable companies exposed to this structural trend.

Going back to first principles, money provides a medium of exchange for goods and services, as well as a common measure and store of value over time, so is generally seen as a useful tool for society. Technology has transformed its use over recent years however, with the rise of online shopping and the often discussed ‘death of the high street’ highlighting a growing shift from physical to digital payment.

There are numerous benefits to this shift: digital payments are more convenient as people no longer need to carry cash and contactless transactions are quicker, easier and more hygienic. Just think for a moment, perhaps not if reading this over lunch, about how many hands the notes and coins in your pockets may have been through in their journey to get to you. Research by MasterCard – which clearly has a horse in this race – found the average UK banknote is home to around 26,000 types of bacteria, including E. coli. For fairness, we should note the new polymer notes are considerably more hygienic.

In recent months however, there has been growing criticism of the digital transition, with a stream of articles across the press. The thrust of this coverage claims a cashless society could leave many outside the financial system, either through simple aversion or inability to access technology or simply general wariness towards a scenario where every purchase leaves a digital trace. Housing charity Shelter estimates there were around 320,000 homeless people in the UK last year and it remains to be seen how this cohort will cope in a digital world.

A recent report called the Access to Cash Review revealed that just three in 10 UK transactions are now in cash and in 15 years’ time, this could be as low as one in 10. The research claims 17% of the population – or eight million people, many of whom are among the country’s poorest – would struggle to adapt and sets out the following five ways to ensure cash remains “viable for the foreseeable future”:

- Ensuring consumers can get cash where they live and avoid so-called ‘cash deserts’

- Taking steps to ensure physical money is still accepted by retailers and other service providers

- Adopting radical change to the wholesale cash infrastructure

- Making sure digital payments are inclusive for everyone in society

- Forcing the government to develop a clear policy on cash

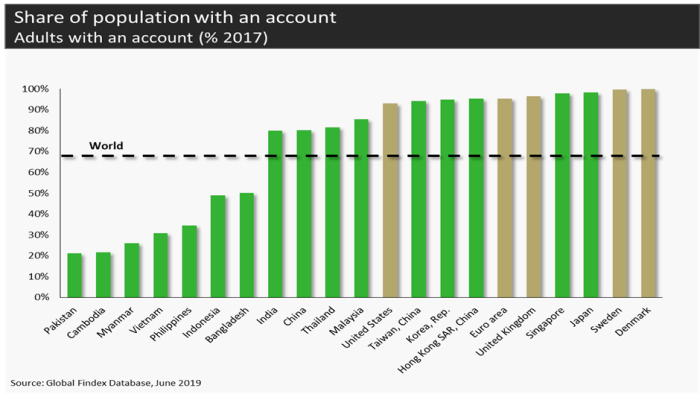

Most sustainable investing involves some kind of trade off and while we recognise these important issues, we would also stress that in underbanked countries, access to a cashless payment and savings system can actually foster financial inclusion. The chart below shows the wide range of banking penetration across the world.

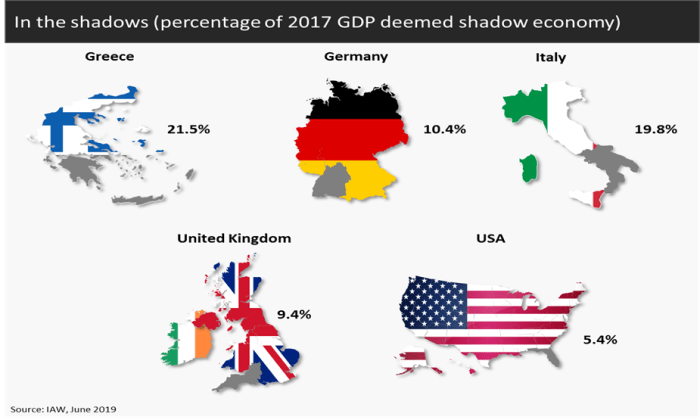

A major factor behind our view that going cashless provides net benefits to society is based on the potential to reduce or resolve the tax gap and expose the so-called shadow economy. There have been many efforts to quantify the cost of such illegal activity globally: in the UK, for example, the Bank of England revealed in 2015 that no more than 50% of notes in circulation are used for domestic transactions and hoarding with the balance either overseas or used in the shadow economy.

In the US, the figures are even starker, as revealed in Ken Rogoff’s 2016 book The curse of cash. In 2015, he calculates the amount of cash in circulation suggests every man, woman and child in the US was walking around with $4,200, 80% of which is apparently in $100 bills.

While some is abroad, some in cash registers and vaults and some lost or destroyed, Rogoff believes a substantial proportion is employed in the underground economy used to buy and sell illegal goods and services, which, by their very nature, tend to lie outside the tax system.

A 2013 report commissioned by the Institute of Economic Affairs defines the shadow economy as “activities and the income derived from them that circumvent or otherwise avoid government regulation, taxation or observation”. In the UK, such activities were estimated to make up around 10% of GDP in 2017, rising to almost 22% for Greece and 20% for Italy.

In the 2014-2015 tax year, HMRC calculated the gap between tax that should theoretically be collected and the amount that actually was to be around £36bn – enough to fund the UK’s Brexit divorce bill or indeed pay for another three or four years of UK membership of the EU. Moving away from the anonymity that cash transactions allow and towards the detailed audit trails inherent in the digital world would, if nothing else, make profiting from illegal activity more difficult.

Beyond this, we see a number of other growth drivers for the digital transition, with the most obvious being the undeniable fact more and more shopping and business is done online and, as this continues, the role of cash clearly diminishes. There are some notable exceptions to this however: in India, for example, cash on delivery remains the dominant payment method and the same is true for Nigeria, the Philippines and Russia.

Rapid expansion in Asia is another tailwind, with data from Capgemini showing cashless transaction volumes are growing seven times faster than in the developed world. Unlike the typical ‘Asian growth driver’ story, however, China is not a major factor here as its digital payment structure is effectively closed off to international players such as Visa and MasterCard that dominate elsewhere. China already has a digital payment ecosystem built by local companies such as Ant Financial (Alipay) and Tencent (WeChat Pay), and both of these have ambitious expansion plans for the overseas market.

With a broad case for our digital payments theme established, the next step in our process is identifying companies exposed to this trend and there are a number of potential areas to investigate, with many stages and players involved in these transactions.

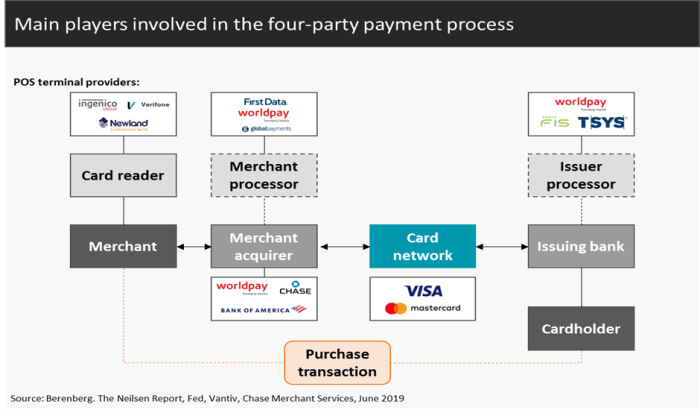

At the simplest level, there are businesses that make the contactless payment machines but the major opportunities we see are in the companies embedded in the transactions themselves. The most common system for card payments is the four-party payment process (shown in the chart below) applied by the likes of Visa and Mastercard, involving the cardholder/consumer, the merchant, the merchant acquirer and the issuer.

Networks such as Visa, a long-term holding in our global funds, fulfil an essential role in this system. The merchant acquirer and card-issuing bank processes the payment on behalf of the merchant and cardholder, while the network provides the central platform that connects the two sides and sets the rules for the transaction.

Visa takes a very small percentage of the value of billions of transactions processed each year and the complex nature of this system, and the crucial role operational excellence plays within it, provides the company with enormous barriers to entry. This is the ultimate scale industry: cost per transaction falls steeply with growth, which results in successful companies becoming harder and harder to dislodge. This scale argument also applies in the merchant acquirer space where, until recently, we held businesses including Worldpay.

Digging deeper into our experience as investors in Worldpay will help illustrate this point. We participated in the IPO that valued Worldpay at £6.3bn in October 2015 and, by August 2017, Vantiv had agreed to acquire the company at a valuation of £8bn, deciding to keep the Worldpay name. In March 2019, Fidelity National Information Services (FIS) announced it was acquiring Worldpay at a 13% premium to the pre-close price and a 21% premium to the 30-day moving average. The deal is being funded by a mix of cash and shares and so is described, in a similar manner to the Vantiv deal, as a ‘merger’. The most recent acquisition by FIS values the company at around £27bn ($35.5bn).

We remain confident the shift to digital payments is a powerful structural trend and continue to look for well-managed, attractively valued businesses exposed to it. In the last quarter of 2018, we took the opportunity to benefit from the market sell off to buy PayPal for our global equity funds and GB Group for the UK equity portfolios.

A cashless society remains an emotive issue that elicits strong reactions: in 2016, Deutsche Bank CEO John Cryan said cash was both costly and inefficient and would no longer exist in 10 years and yet the amount of cash in circulation has actually grown rather than shrunk.

However people feel about these underlying questions, we would end by pointing out one simple fact: despite the rapid digital shift in the developed world, 85% of payments globally are still made in cash, which creates a huge growth opportunity as technology continues to improve and any lingering aversion to it erodes.

KEY RISKS

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and the income generated from it can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. You may get back less than you originally invested.

The issue of units/shares in Liontrust Funds may be subject to an initial charge, which will have an impact on the realisable value of the investment, particularly in the short term. Investments should always be considered as long term.

Some of the Funds managed by the Sustainable Future team involve foreign currencies and may be subject to fluctuations in value due to movements in exchange rates. Investment in Funds managed by the Sustainable Future team involves foreign currencies and may be subject to fluctuations in value due to movements in exchange rates. The value of fixed income securities will fall if the issuer is unable to repay its debt or has its credit rating reduced. Generally, the higher the perceived credit risk of the issuer, the higher the rate of interest. Some Funds may invest in derivatives. The use of derivatives may create leverage or gearing. A relatively small movement in the value of a derivative's underlying investment may have a larger impact, positive or negative, on the value of a fund than if the underlying investment was held instead.

DISCLAIMER

This is a marketing communication. Before making an investment, you should read the relevant Prospectus and the Key Investor Information Document (KIID), which provide full product details including investment charges and risks. These documents can be obtained, free of charge, from www.liontrust.co.uk or direct from Liontrust. Always research your own investments. If you are not a professional investor please consult a regulated financial adviser regarding the suitability of such an investment for you and your personal circumstances.

This should not be construed as advice for investment in any product or security mentioned, an offer to buy or sell units/shares of Funds mentioned, or a solicitation to purchase securities in any company or investment product. Examples of stocks are provided for general information only to demonstrate our investment philosophy. The investment being promoted is for units in a fund, not directly in the underlying assets. It contains information and analysis that is believed to be accurate at the time of publication, but is subject to change without notice. Whilst care has been taken in compiling the content of this document, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made by Liontrust as to its accuracy or completeness, including for external sources (which may have been used) which have not been verified. It should not be copied, forwarded, reproduced, divulged or otherwise distributed in any form whether by way of fax, email, oral or otherwise, in whole or in part without the express and prior written consent of Liontrust.